D. Capacity for Performance

85. Addressing the performance challenges presented in this chapter will require strengthening staff capacity. The analysis shows that implementing staff and human resource (HR) measures can help increase utility performance. Using the information in IBNET related to HR,30 one can differentiate utilities according to the HR measures or incentive schemes the utility management employs. As Figure 51 shows, the WUPI scores of utilities employing HR measures are significantly higher compared to utilities without such measures. While it is hard to pinpoint the measures that have the highest impact, the results indicate that using a set of measures is more effective than only a single approach. The effects of HR measures is most clearly visible in the WUPI subcomponent “WUPI management.” This is hardly surprising because professionalized staff can help to improve business practices—most of which are part of WUPI management— but has probably less of an effect on performance indicators that require capital investment (e.g., WUPI coverage).

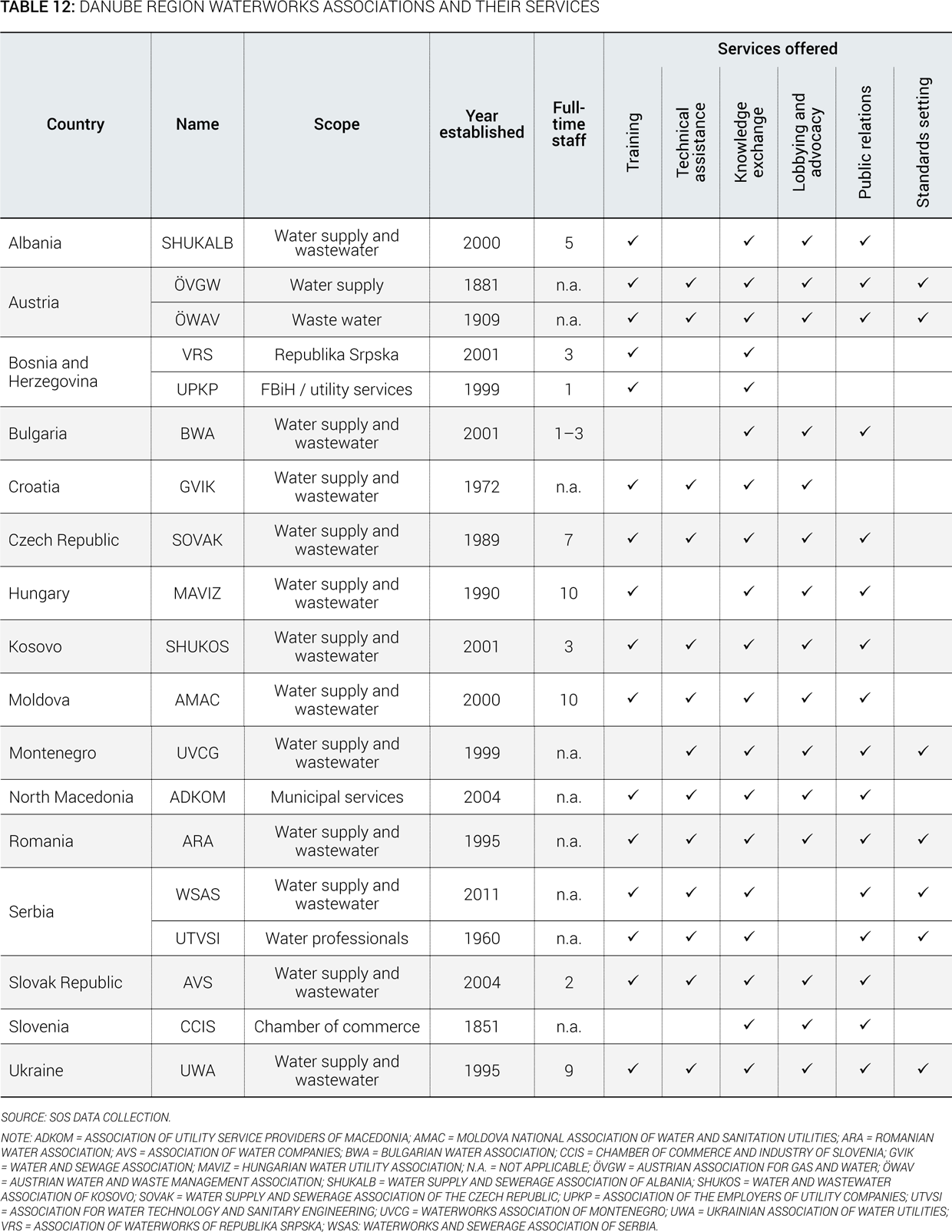

86. Utility associations can help foster capacity building of their member utilities. All countries in the region have a utility association covering either water supply, wastewater, or both sectors (Table 12). These associations have their own operating budgets and staff. Most of them provide knowledge exchange, training, and public relations services to their members, while a few also set technical standards. In addition, since the last review a number of initiatives have begun consolidating capacity building activities in the region, such as under the Danube Learning Partnership (D-LeaP) (see box 9) and the Regional Capacity Development Network (RCDN).

Box 9 Danube Learning Partnership

D-LeaP is a regional, integrated, and sustainable capacity building initiative of national water utility associations and the International Association of Water Service Companies in the Danube River Catchment Area (IAWD), and provides a comprehensive curriculum to the staff of water and wastewater utilities in the Danube region. D-LeaP is a committee of IAWD, comprising representatives of national water utility associations.

The primary target audience of D-LeaP programs consists of the water supply and wastewater utility companies in the Danube region and their management and technical staff. Of the 17 countries covered by D-LeaP, utilities in 12 countries are expected to have a particular interest in D-LeaP programs based on the level of development of their utility sector: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, and Ukraine.

SOURCE: D-LEAP WEBSITE, HTTPS://WWW.D-LEAP.ORG/.

87. Raising awareness about workforce diversity, especially on gender imbalance in water utilities staff, continues to be a challenge—despite its importance for strengthening the sector’s capacity—although dialogue has begun in some pioneering utilities of the region. Many countries have policies or laws addressing gender balance issues, but few are translated into strategies and are not targeted toward the WSS nor have they been sufficiently backed by adequate resources. When looking at the WSS sector specifically, women’s participation as staff or engineers is still low (Table 13). In Slovenia, for instance, among the 102 utilities, only eight CEOs are female. Austria is the only country reporting that some utilities take actions to address gender imbalance. Despite this, positive developments are observed with a number of utilities engaging in assessments to better understand gender and age related issues in their workforce (See Box 10).

Box 10 Case Study: Gender Assessments in Three Danube Region

Around the globe, an increasing number of private and public companies are realizing that promoting gender equality in the workplace is good for business and development. In the Danube region, utilities often face a predominantly male and sometimes aging workforce. However, gender gaps in tertiary education including in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics are gradually closing. For the water sector, creating an environment with equal opportunities for men and women at all levels of responsibility and an inclusive work culture should thus be an integral part of every utility’s modernization process.

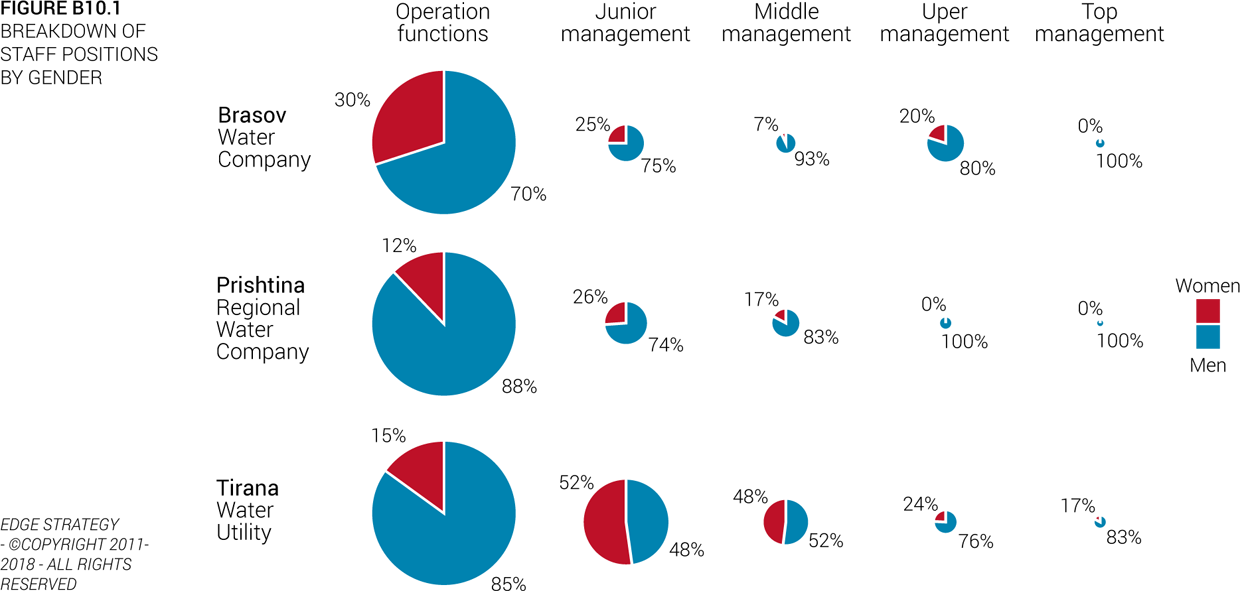

In 2018, the DWP and the World Bank Global Water Security and Sanitation Partnership collaborated with three pioneering utilities in the Danube region to take a closer look at gender equality in their workplace. The Brasov Regional Water Utility in Romania, the Prishtina Regional Water Utility in Kosovo, and the Tirana Water Utility in Albania undertook a gender assessment, using a globally certified methodology (http://edge-cert.org/).

The assessment shows that all three utilities scored above the EDGE international standard for gender equality in junior management positions; however, they fell short in terms of top management, and none of the utilities had any women sitting on their boards (see Figure B10.1). In terms of career trajectory, at the operational level, male staff were more likely to be promoted than female staff, and men were more likely to be recruited to junior management positions. In all three utilities, men were systematically more likely than women to be promoted at all levels of operations and management. At Brasov Water Company, women are more likely to stay in the same position or make a lateral move at the junior management and upper management levels while men are more likely to make that transition at the middle and top management levels. At Prishtina Regional Water Company, women are more likely to stay in the same position or make a lateral move at the junior management level, while men are more likely to make that transition at the upper and top management levels. Finally, at Tirana Water Utility, men and women are equally likely to stay in the same position or make a lateral move across all levels of responsibility.

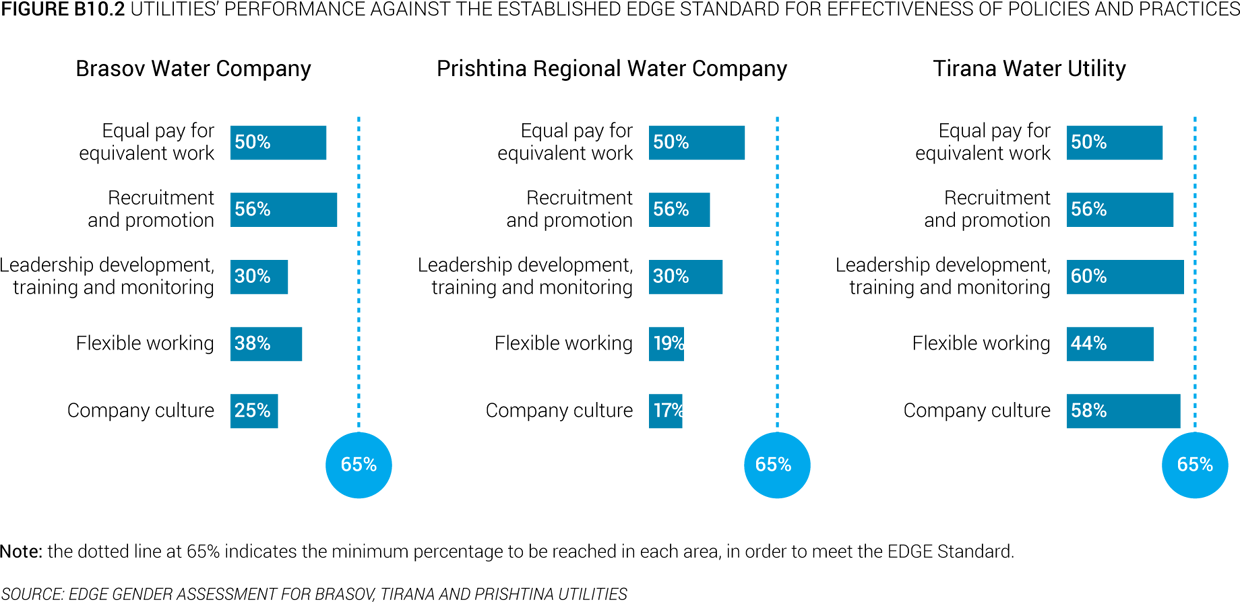

When looking at effectiveness of policies and practices, while all three utilities demonstrate some degree of proactiveness when it comes to equal pay for equivalent work, there is still room for improvement (See Figure B10.2). None of the three companies have a specific policy when it comes to equal pay for equivalent work. No gender pay gap assessment is routinely done by the utilities, although this measure was introduced by Brasov for the first time. In addition, none of the three utilities have set targets or objectives for the gender compositions at any management level, and the Brasov Water Company and Prishtina Regional Water Company do not take the gender dimension into consideration in their success planning. However, all three companies have flexible promotion practices that systematically accommodate flexible promotion rhythms, do not require geographical mobility, and allow career breaks. Performance evaluation processes could be improved in all utilities, and systematic mechanisms to identify high performing staff are in place. Finally, nondiscrimination with regard to professional development is demanded by the law. Therefore, none of the three utilities have formulated a specific policy in this respect, though perception of such opportunities show a gender gap in some utilities. When it comes to mentoring and sponsorship, none demonstrated having formal mentoring programs for men and women. Flexible working practices are mostly used informally, but good examples were found, especially when initiated by staff themselves (e.g. the organization of weekend shifts in Prishtina laboratory, a unit that employs a significant number of women) and further technological innovations can be expected to facilitate such practices in the future, calling for more formal and transparent policies.

Regarding employees’ perceptions of an inclusive culture, most employees across all three utilities consider that women and men are given the same opportunities to be hired (with the exception of women at the Brasov Water Company, in which 49 percent of women answered positively). Respondents were less optimistic when asked whether there were fair opportunities to be promoted across all three utilities. When it comes to being paid fairly for the work that they do compared to others in the utilities, employees were slightly more negative across utilities. In all cases, a notable gender gap in perceptions was found, with men being more optimistic than women on these questions. A gender pay gap assessment would shed light on whether these perceptions are based on evidence. In the case of the Brasov utility, such negative perceptions were not founded in facts, pointing to the need for clear, consistent, and transparent communication to employees.

Gender pay gap. The unexplained gender salary gap in the Brasov utility is 13 percent in favor of women, although narrowed to only 5 percent when salary and bonuses are included. The unexplained gender pay gap means that pay differences are not explained by factors such as age, years with the company, management role, level of responsibility, or job function, but are likely to be explained by gender. The utility is refining this analysis to understand how performance ratings impact on these results. The assessment allows for the identification of priority challenges and an action plan. The utilities have each self-identified three priorities, such as (i) conducting yearly gender pay gap assessments, (ii) improving the transparency of the promotion process and promotion criteria, or (iii) implementing a systematic procedure to identify top talents, and are addressing those. In addition, they have been sharing their experience with other water utilities in the region through regional knowledge exchange events, leading to lively debate and discussion, indicating the relevance of the topic to utility staff and sector professionals.

This is an important development in the region’s WSS sector, from one in which gender considerations were not discussed to one in which utilities are actively seeking a better understanding of how they are doing, and how an inclusive workforce can be translated to better utility management. With a transformation of utilities and new incoming workforce of younger males and females, the management of human assets is increasingly recognized to be equally important as management of physical assets.